One may notice that my pictures of photographing waterfalls are often tight shots of part of the waterfall. There are two components to this choice – practical and the aesthetic.

Practical

From a practical standpoint, the waterfall is ‘big’. Even something that is “only” 15 feet tall is still bigger than a photograph of a person (and often with people, we take portraits rather than full body photographs).

When photographing a waterfall, there are three key restrictions – lighting, location and landscape. Neither of these the photographer has too much control over.

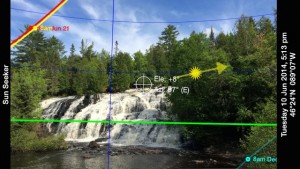

With the light – the only choices the photographer has are time of day, day of year, and the weather. While this is a choice, it isn’t something that one can say “lets put a flash over here and a hot light over there…” The waterfall is too big to try to photograph as if it was a studio shoot. If you want a soft box, you have to wait for the right clouds. If you want the light from over there, you pull out an app on your smart phone and figure out where the sun will be over there (or if you are pre-planning, the naval observatory sun/moon altitude/azimuth table and a topo map (though that doesn’t know about trees).

With the light – the only choices the photographer has are time of day, day of year, and the weather. While this is a choice, it isn’t something that one can say “lets put a flash over here and a hot light over there…” The waterfall is too big to try to photograph as if it was a studio shoot. If you want a soft box, you have to wait for the right clouds. If you want the light from over there, you pull out an app on your smart phone and figure out where the sun will be over there (or if you are pre-planning, the naval observatory sun/moon altitude/azimuth table and a topo map (though that doesn’t know about trees).

With the location, while sometimes you may be able to jump off a trail and hike around to where you really want to be, this isn’t always possible or practical. Sometimes the parks may forbid it, other times you just can’t get there.

And lastly, landscape. Some waterfalls have spectacular open areas before them that allow the light to fully illuminate them (or keep them in shade). Other waterfalls have things like trees, or bridges, or cliffs that prevent. I know photographers who have grumbled and joked – threatening to bring chainsaws with them to remove particular trees that mar the scene.

So, with these things conspiring, you really can’t change too much about a waterfall. Its there, and its going to stay there, and the sun is going to move. So, sometimes, with some types of waterfalls (the ones I am most drawn to), the dynamic range of the entirety of the waterfall is just too great to try to capture.

High dynamic range really isn’t the solution either. Sometimes (less commonly now, but still sometimes) I find myself shooting film and that really doesn’t let you do HDR outside of the film choice. Digital HDR isn’t too much of a solution either because of the nature of the waterfall and its constantly changing flow. Its better now than it used to be, but between the motion and my personal dislike of it, its not what I want to do.

And so, I pull out a long lens and photograph a small section of the waterfall. I can often find part of it that is ‘right’ and has a fairly narrow range, allowing me to capture it.

Aesthetics

Now, for some aesthetic aspects of this…

Multnomah Falls

Some waterfalls are a single, crystal song where all of the water is singing a single note. These are the ‘pure’ waterfalls that often have names like bridal veil.

Lower Yellowstone Falls

Other waterfalls, are a roar of a thousand voices all shouting “Geronimo!” as the water plummets over the brink.

But for me, I like something that is a bit more of a “choir”. It could be a small quartets or one with hundreds of voices to it. And I like to pick out one piece of the song that is the waterfall, and concentrate on just that spot. Just where that water flows and how its framed by the rest of the waterfall.

Burney Falls

When composing, ideally, one can follow the water through the frame with one’s eye. It starts here, it flows through the photograph here, and it flows out there. There is a single melody pulled out of the song of the waterfall, a single story of some water from the surrounding waterfall.

With the pure note waterfalls, there’s no individual story that can be pulled out of it – they’re all singing the same song. With the roar over the brink – they are impressive in their shear power, but there is no hope at all of pulling out one melody out of it – its lost in the volume of all of the rest of the water.

And so, instead of a 17mm lens to photograph the waterfall, I’m more likely to start at 70mm and end up somewhere between 135mm and 400mm depending on the situation. The small piece of the waterfall is much more interesting to me than trying to capture it all.

codemore code

~~~~